I've never been too subtle

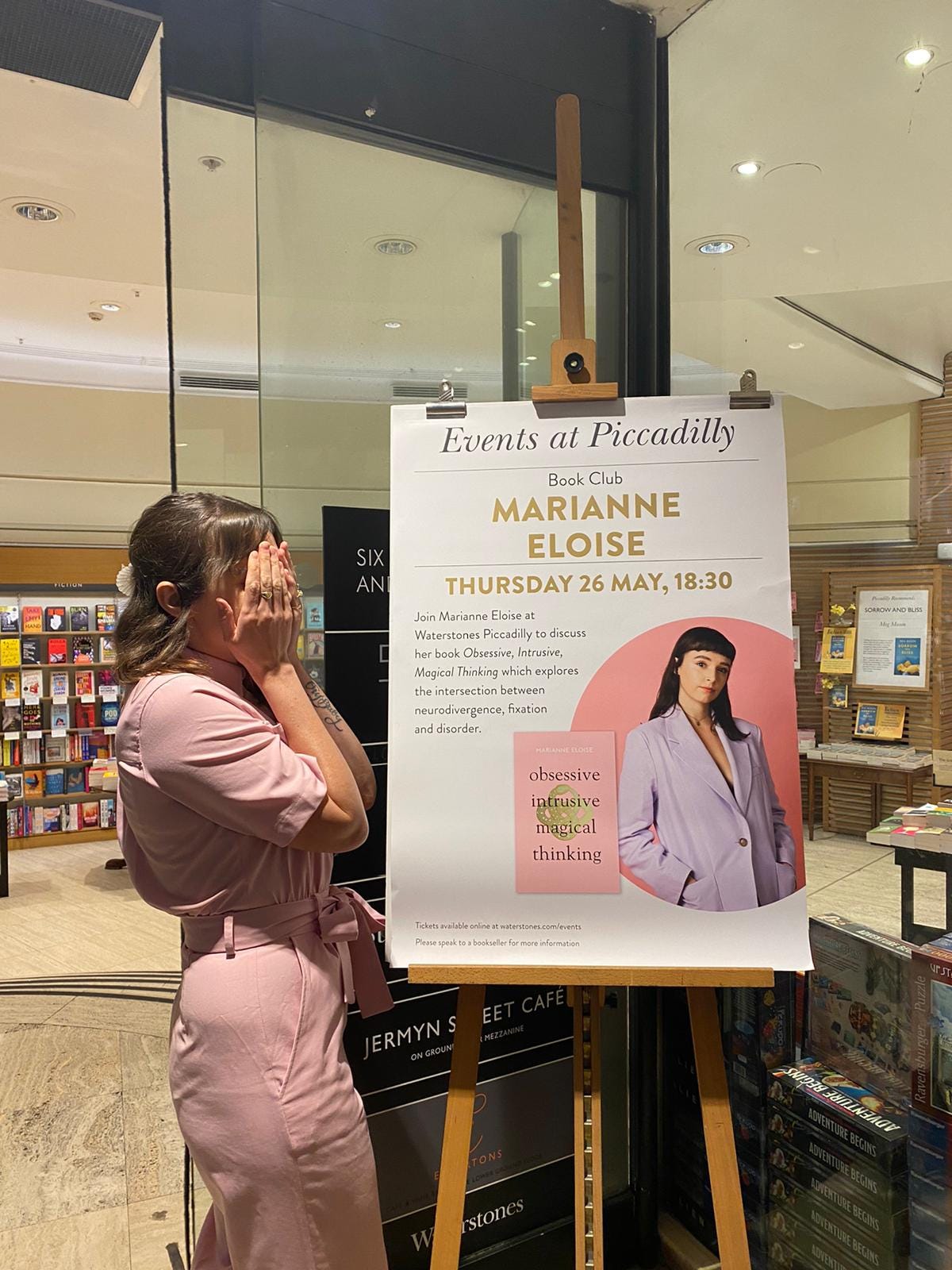

Three years of a pink book named after this blog

There is a hateful derision directed at people, in particular women, who write about their own lives. I knew this when I pitched Obsessive, Intrusive, Magical Thinking, an essay collection about my overactive brain, but I did it anyway. On their own, the essays were about things I had been fixated on throughout my short life: fire, my own body, death, Disneyland, Medusa. Overall, they painted a picture of a person grappling with their own neuroses and trying to separate what is them and what is neurodivergence or mental illness.

I am autistic, and this is something I have come to realise I cannot change. That, along with childhood abuse and neglect, left me vulnerable to obsessive conditions like OCD and an eating disorder. Throughout the book, I detail my journey recovering from those neuroses while learning that there are some things that are fundamental to who I am. I mostly recovered from my eating disorder and OCD around the age of 19 or 20, when I moved out of my abusive household. The autism, however, just won’t shake.

I was 27 when I began writing the book, 29 when it was published. People rightly said that this was too young to publish something they saw as a memoir, but I never intended it to be one. It might not seem it, but the scope of the book is quite narrow. I hone in on specifics, on small obsessions that say something about myself without giving everything away. I gave exactly what I felt comfortable with. I elided some parts of my life without lying. I was as vulnerable as I felt I could be safely.

I was very aware, while writing, that any person could take issue with any aspect of who I am and what I have done. Still, I am not ashamed of having struggled with mental illness, of having battled starvation and self harm as a teenager. I am proud that I recovered from these issues mostly without even the help of therapy. I came from a very difficult, violent background and did not have many opportunities for safety or healing, particularly as an adolescent. I found, and built, my own safe life. With a little help from my friends.

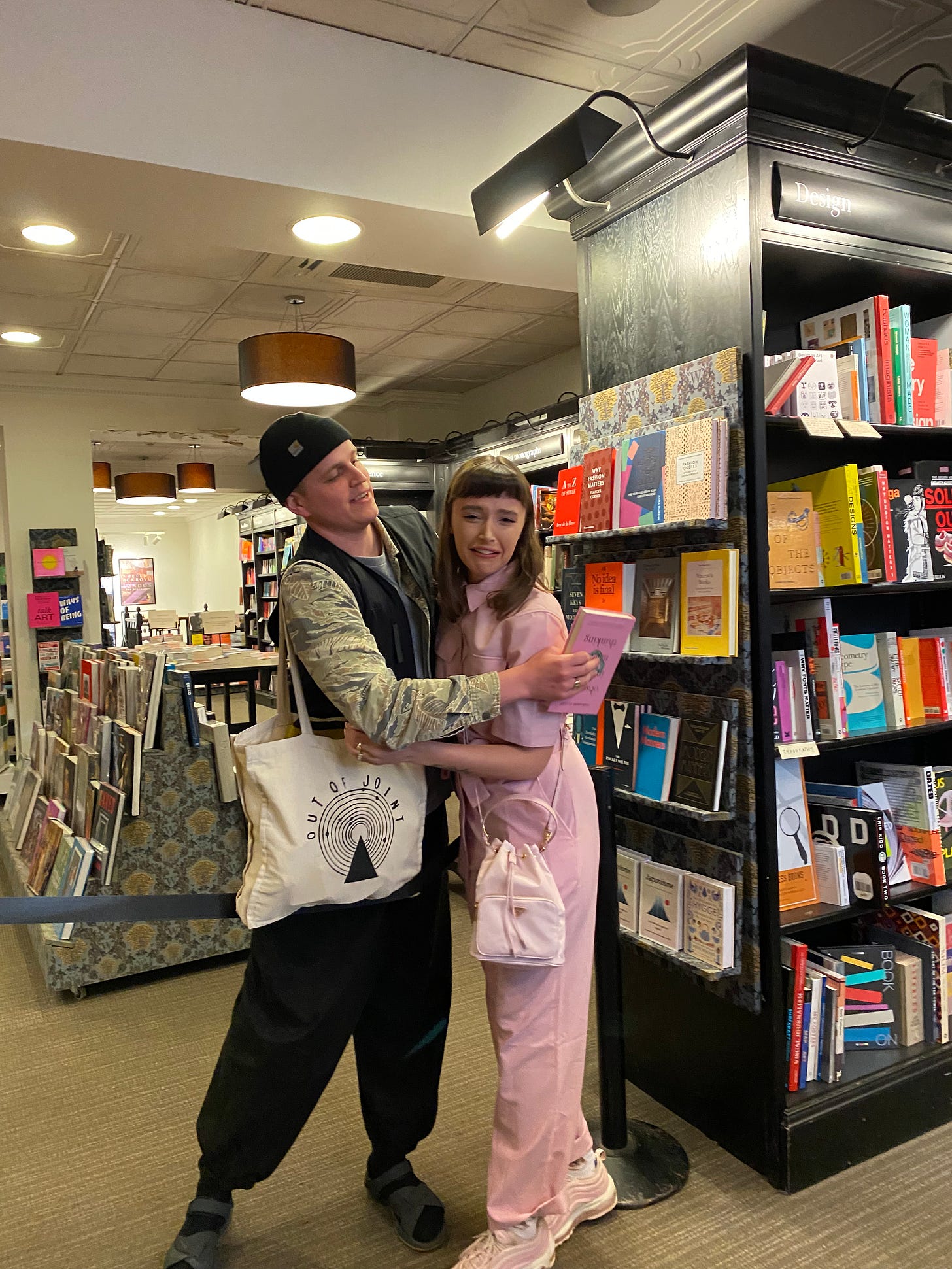

The book came out during a difficult time, and it exacerbated anything I already had going on. I celebrated its release at an event with my closest friends, some of whom travelled far to celebrate with me. I cried a lot. I did a lot of interviews, and I liked how I came across in some more than others. I had my photo taken and I put on and spoke at events in London, LA, Brighton and other cities. I wore the same pink outfit over and over again to talk to crying autistic people about what me writing about my own life meant to them.

This time was at once meaningful and sincerely overwhelming. I received a lot of messages, some of them essay length, not all of which I could respond to. Other people got tattoos relating to the book. I felt like I could never live up to what I represented in those people’s minds. There were at least two very different versions of me, and I was neither as reprehensible nor as relatable or virtuous as people wanted me to be. I was a person, and I was struggling a lot.

That only got more true as the months went on. The book was released in April, and in May my grandad told me he was dying. He read the book, several times, noting down questions to ask me. He cried that he couldn’t have done more for me when I was growing up, but I had always felt he’d done more than enough. Over the summer, I planned a wedding while spending every second I could with him. My grandad died in July, six weeks before I got married.

Throughout this time, I did interviews and events and hid from the world as much as I could while still keeping up my promotional obligations. Once, a friend interviewed me and told me that I romanticised life, asked if the way I only focused on the things I liked about the world was deliberate. I burst into tears and told her that my grandad was dying, begged her not to include it. She was right–I did have a tendency to tilt my hand, to only show the summer’s sea swimming and days at the beach and wedding planning and to occlude the crushing weight of grief.

I thought if I laid out my life plainly, it would be read in good faith. Of course, I was wrong. One notable example: a website that publishes transphobic screeds asked for a copy, and I told my publisher to refuse, knowing what their angle would be. They had a middle-aged male blogger write an article entitled “Mental Illness Doesn’t Make You Special”, in which he made a number of assertions, most of which were untrue.

For example: that I claim to have done “lots of drugs”. The section he refers to as evidence is me talking about a dream I had wherein I did lots of drugs. Later, he took me saying I had tried every treatment for chronic migraine as evidence of my being a drug addict. He claimed that I have rich parents who fund my lifestyle and vacations. I do not speak to either of my abusive parents, and my mother is on benefits, as she was for many years before I moved out as a teenager. The most egregious lie, maybe, is that I moved to Los Angeles to become an actor–I simply did not.

Of course, this is a result of his having an angle and a lack of reading comprehension. He made a lazy skim-read, looking for the most shocking parts to prove his point. That point was that I am a rich, spoiled girl who languishes in her mental illness. I know that his anger is not at me, but at an idea of someone like me. Still, when I eventually responded (flippantly) to his piece, Goodreads review and multiple Substack blogs referencing me and my book, he posted yet another blog about it tripling down. When I emailed to talk about it, he only got angrier, demanding to know who paid for my £400 trip to Portugal when I was 25 (I’ll confess, it was me).

I have thought about it a lot, and I think people sometimes find it hard to believe that you could actually come from a background like mine, with a brain and body like mine, and live a good and happy life. Some readers held similar sentiments–that I must be faking being autistic, that I love being mentally ill, that I am spoiled. You would think, perhaps, that I would regret giving so much away so young. I am a naïve person. I think the best of most people without evidence to the contrary, and I tend to believe that if I am honest, everyone else will be too.

When I wrote that book, I wanted to share what it feels like to live in my head. I hoped some people might relate to it, but mostly I just wanted to process my life to that point. I wanted to convey that there is no shame in being autistic and that you can heal from the difficult parts of living with your brain while not losing the core of who you are. I want to be living proof that no matter how shittily you are treated in the first part of your life, you can build something better than you were taught you deserve.

I knew some people would read it cynically, even cruelly. I was surprised at the extent a person could go to, however. I cried a lot, wanting to be left alone, but also to be understood. It is hard to believe that you have laid out exactly who you are and to still have people read you all wrong. I did not anticipate that a grown man could get so incensed at the story of a teenager’s recovery and a young adult’s acceptance of how their brain works that they would write multiple blogs misinterpreting it. That’s on me.

I haven’t really talked about that before before because I wanted the whole thing to disappear and it is embarrassing to admit that someone rattled you. Still, I am not ashamed to admit that I found the entire exchange quite scary. That I could be that misunderstood and that someone else’s misunderstanding could drive them to anger. I have been writing about my own life for a long time, and I am familiar with the cycle. I have had mean comments, scathing emails, hate-follows. Still, I just won’t stop! But I don’t think it’s masochism. I have kept a diary since I was 11 years old, and it’s the only way I know to process how I feel and what I’ve experienced.

If I have any regrets, it might not be being honest, but being so coy. While it takes a degree of dishonesty to presume I grew up rich, it probably is difficult to pick up the specifics of my upbringing from what I shared. I referenced my childhood poverty and my mother’s alcoholism and abuse obliquely. I did that to protect my sister, who I tried to raise but who was still living at home. She no longer is, for many of the same reasons that I moved out in the first place. Maybe some part of me did it to protect my mother, or at least to avoid her reaction. I am still so scared of her.

Since that book was published, however, she has behaved in ways that even I thought were beneath her. I cut off contact with her in the summer of 2022, and I don’t know if I would have protected her had the book come out later.

When I wrote that book, I was in lockdown, missing the world. I wanted to preserve it the way I remembered it, the beautiful things I had been lucky to see and do. I was fearing and anticipating the death of my grandad despite his apparent good health. I was reflecting on how far I had come, that the life I was living was so far from the one I thought was possible for someone like me. I am proud of who I was then, and that I was brave enough to share so much of myself. Despite the weight of expectation, the gratitude of people who took something from my book has made some of the difficult parts worth it.

Writing that book was naïve. It is naïve to believe that you can simply say what you mean and that people will believe you. Maybe I am naïve! I am sure I will always make the mistake of thinking it’s safe to share the most tender parts of myself, of believing that if I say what I mean then people will take me at my word. I would rather be this way than a cruel cynic looking for the worst in total strangers. I might write that book differently today, but I don’t regret doing it. I am proud of that slightly younger person.

I am so proud of you and the life you’ve built for yourself 💖 you are the strongest person I know